Heliset Tte Skal – Let the Languages Live Conference

We supported Professor Rawinia Higgins, Chairperson and Commissioner of Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori – The Māori Language Commission and Charisma Rangipunga, Deputy Chair of the Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori Board of Commissioners, to attend the Heliset Tte Skal – Let the Languages Live conference in Canada from 24-26 June 2019. Rawinia reports back.

Rawinia reflects

The Heliset Tte Skal – Let the Languages Live conference was held at the Victoria Convention Centre, Victoria, British Columbia in Canada and over 1000 participants were registered for this conference. As part of the UNESCO Year of Indigenous Languages celebrations, the conference was not only informative but also presented a diverse range of topics as part of the line up of speakers.

The conference was opened by the local indigenous people, and a performance by their children who are part of their local immersion school. They performed a number of items that the children had learnt as part of their curriculum and led by a number of their elders. This was followed by an address by the Chair of the organising committee Tracey Herbet and a welcome from Songhees with Chief Ron Sam and Regional Chief Terry Teegee.

After the indigenous ceremonial welcome was a pre-recorded video of His Royal Highness, Prince Charles, the Prince of Wales. As part of his welcoming speech, he discussed a commitment by his Prince of Wales Trust in Canada to support indigenous languages as part of their priorities for the year. He was pleased to be included in the conference and hoped that his work would continue to support the efforts of indigenous peoples in Canada.

One of the highlights of the conference was an address by the National Chief, Perry Belgarde, whose keynote address focused on the recently passed Indigenous Languages Act in Canada. It was evident that the National Chief was passionate about the work to achieve the legislation and his impassioned speech was compelling. He shared with the audience how the week prior to the conference he was able to partake in the ascession of legislation by their Governor General and how this marked a significant milestone in their history. He outlined how the legislation gave indigenous languages in Canada the opportunity to establish a Language Commission with support from the Government.

As the National Chief outlined the opportunities the new legislation provided them, it allowed me to reflect on how far te reo Māori has progressed in Aotearoa New Zealand. It was evident throughout the speech that Canada is approximately where we were in 1987 when our first Māori Language Act was passed. With respect to our then legislation, it also enabled us to establish Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori – The Māori Language Commission, it provided funding for language initiatives and government recognition of languages. Although they have some way to go, particularly as they move to establish their Commission, as the Māori Language Commissioner it was pleasing to see that we have paved the way for indigenous languages at an international level. Other examples of how this resonated was the continual references to the initiatives that they were supporting including ʻlanguage nestsʻ (modelled on Kōhanga Reo) and immersion schooling (Kura Kaupapa Māori). This was further reinforced by one of the other keynote speakers, Professor Larry Kimura from Hawaiʻi, which I will discuss later.

Another observation that I made as a result of listening to the very moving and impassioned speech by the National Chief, was his sense that in order for language revitalisation to be successful that it needed to rely on the government. There was very little reference for language in the homes or for intergenerational transmission. This was an issue that I would later raise as part of the panel presentation I gave that followed.

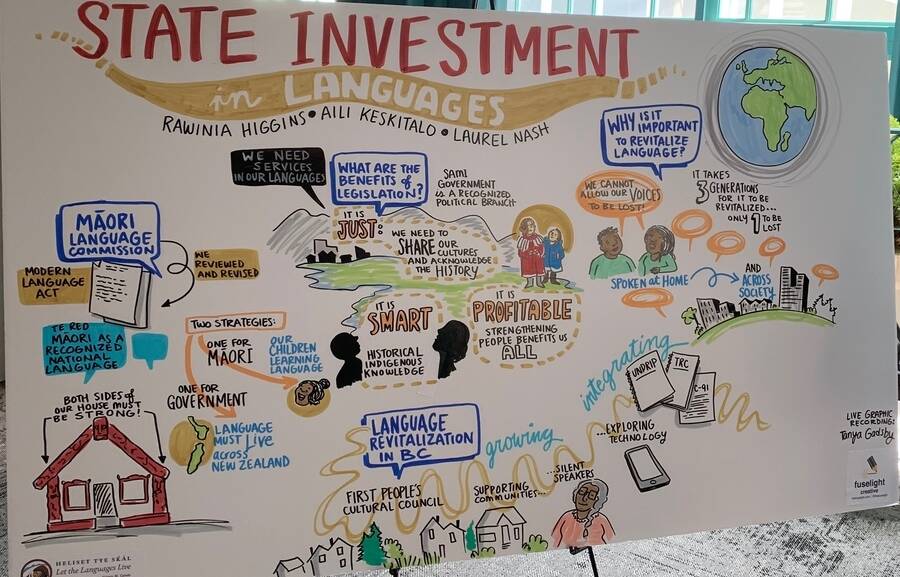

Following on from the first keynote speaker, I presented on a panel focussing on ‘State Investment in Languages’ alongside Laurel Nash, Assistant Deputy Minister – Environmental Protection Division, Ministry of the Environment Canada (previously from the Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation) and Aili Keskitalo from the Saami nation in Finland. This session was held in the main auditorium with the majority of the conference participants attending. This panel provided an opportunity to present the current situations in our respective countries and the impact of state investments on language revitalisation.

Aili Keskitalo had three key messages about why governments should support indigenous languages, namely:

- It is just – recognition for them as the indigenous communities of their country

- It is smart – understanding their language and culture promotes a stronger sense of understanding of themselves

- It is profitable – provides a number of benefits for the whole nation.

Laurel Nash described some of the efforts and priorities that were occurring, particularly in British Columbia, which included:

- First Peoples Cultural Council, setting the priorities for their area with respect to language revitalisation

- Supporting communities with initiatives, including but not limited to the Silent Speakers initiatives. This initiative was recording elders and encouraging them to record their native languages before they pass on. For many of them this can be highly emotive as many of them have not spoken their languages since they were young

- The use of technology as a mechanism to record and archive their language but disseminate their language to people

- The current focus on developing the legislation leveraging off other examples including the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

My presentation focused on the development and implementation of Te Ture mō te Reo Māori 2016. More specifically:

- The development of Te Whare o Te Reo Mauriora and the role of Māori and the Crown in developing two new language strategies (Maihi Māori and Maihi Karauna)

- The current role of Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori to lead the coordination and implementation of the governmentʻs Māori language strategy which aims to reach one million speakers by 2040

- The need for te reo Māori to be viewed as our nationʻs language and for a coordinated effort by Māori and government in future efforts

- The importance of intergenerational language in whānau, reminding people that ʻit takes one generation to lose a language and three generations to restore this’ – this required a joint effort between Māori communities and the government

- The importance of ensuring that indigenous peoples have a voice in determining the initiatives needed to support language revitalisation.

The panel was well received and a number of people approached me afterwards to continue discussions around the Maihi Karauna but also the whare in general. One of the staff members from the government asked to have a further conversation about the establishment of their language commission, which we hope will eventuate. Initial emails have been exchanged with a hope that we can continue with this discussion.

Parallel sessions continued for the rest of the day. Some examples of themes in parallel sessions included (but were not limited to):

- Nationwide language planning/large initiatives

- Consciousness application strategies when making space for language in the home

- Fluency approaches

- Creating adult speakers

- Language and digital technologies

- Archive based research for revitalisation

- Story telling

- Music and language

- Youth involvement in language revitalisation

- Planning in Language Domains

- Legislation and public services

- Elders and language revitalisation

- Curriculum development

- Literacy

- Spirituality

- Dictionary development.

The afternoon keynotes included the Honourable Carolyn Bennett, Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations. Her address focused on the passing of the recent legislation and the governmentʻs role in supporting the recognition of indigenous languages in Canada. As she has a health background, she also spoke about the wellbeing benefits of indigenous languages as another objective in supporting the legislation but also as a means of working towards issues of reconciliation.

The following keynote was Professor Larry Kimura, who shared the Hawaiian experience that had been modelled off the Māori experience. It described how their efforts had been driven by a number of staff and students from the University of Hawaiʻi in Hilo, who were second language speakers wanting their children to become native language speakers. Their efforts reflected the Māori effort, namely the establishment of their equivalent of Kōhanga Reo and Kura Kaupapa Māori. He also spoke about how they continued to build up their efforts to ensure that there were educational pathways for these students to continue studying their language from school to doctoral studies. Although this experience reflects the Māori experience, he discussed the challenges of the state and gaining government support for their initiatives. He highlighted how their success is largely attributed to the commitment by the initial whānau members who committed to the languge as part of their whānau.

The following day opened again with a keynote address from Dr Lorna Williams a Professor Emeritus from the University of Victoria and Indigenous Education Director and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous knowledge and learning. She discussed some of the challenges of language revitalisation and how these must be brought forward and acknowledged so that they can be worked through. She provided personal insights and examples from communities as a way to unpack these challenges.

More parallel sessions continued after this, however, unfortunately we had to leave the conference at this point to catch our flight to Toronto to attend the International Association of Language Commissioners conference that I was also due to present at the following day. I was disappointed to have to leave the conference at this point as I was keen to hear more from the rest of the keynote speakers and the topics in the parallel sessions. However, it was a privilege to have been included in the programme and to share our experiences with the indigenous communities who attended this conference. It was a good opportunity to get some perspective on our Aotearoa New Zealand efforts but also to see that the efforts of Māori have been adopted by other indigenous peoples across the world.