Learnings from the Adaptations Future Conference

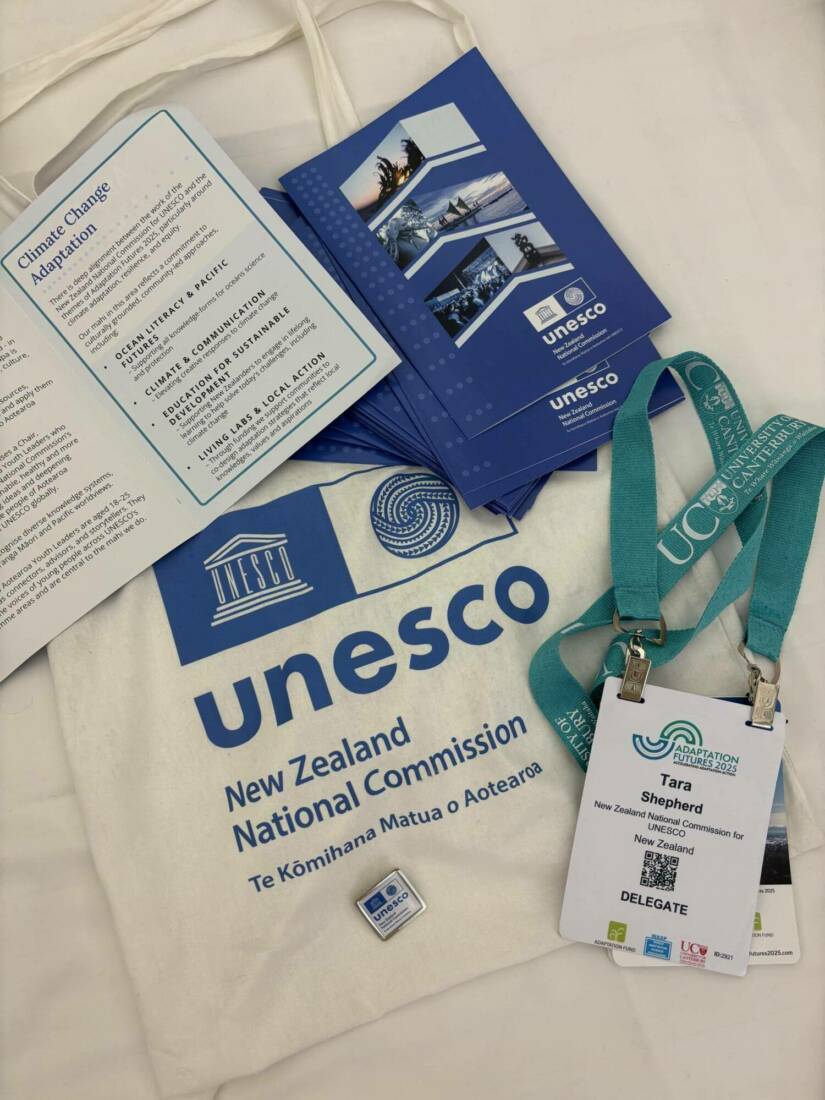

UNESCO Aotearoa Youth Leader Tara Shepherd shares her insights and takeaways from the 2025 Adaptations Future Conference.

Adaptation Futures 2025

Adaptation Futures 2025, now in its eighth year, is the flagship conference of the World Adaptation Science Programme (WASP). This year, Ōtautahi Christchurch had the privilege of welcoming more than 1,800 attendees from over 90 countries, giving the city a chance to showcase its unique blend of natural harmony, innovation, and resilient post-earthquake recovery.

A wide range of professionals, practitioners, academics, technical experts, and organisational representatives convened to not only discuss but genuinely listen. Across workshops and panels, kōrero was grounded in community and partnership, creating a space where co-creation felt intentional and empowered. Participants were encouraged to value Indigenous knowledge alongside academic principles, a powerful reminder that the most effective adaptation pathways are those built on unity and shared understanding.

Aotearoa New Zealand can be proud of the strong presence of local Indigenous voices, including those who led wānanga culminating in the launch of a global Indigenous network. This network aims to strengthen commonalities, recognise barriers to climate finance, and advance collaborative responses to climate change. Among the leaders were Lisa Tumahai (Ngāi Tahu), Deputy Chair of the NZ Climate Commission, and Tagaloa Cooper (Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi, Niue), Director of the Climate Change Resilient Programme at SPREP in Samoa.

These themes resonated throughout the opening plenaries. Lisa Tumahai captured the heart of the dialogue when she said, “They may have the watches, but we have the time,” referring to how scientific and technological advances continue to validate knowledge long held, practised, and shared by Indigenous communities. WASP Chair Chizuru Aoki echoed this sentiment, emphasising “the need for global solutions to be led by local leaders,” grounded in trust and long-term relationships with Indigenous peoples.

Youth leadership also took centre stage, with powerful contributions from voices like Cynthia Houniuhi of the Solomon Islands, President of the Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change and part of the groundbreaking case brought to the International Court of Justice. In her plenary remarks, she reminded us that “the Pacific is the lowest contributor [to climate change] yet faces the highest repercussions,” highlighting how ambiguity in international processes has been exploited by major emitting nations. When asked whether she still has hope, she shared: “At COP meetings, countries struggle to reach consensus. But in side events, young people from around the world unite under one campaign — that gives me hope. If young people can achieve consensus, that is the future.”

Youssef Nassef, Director of Adaptation at the UNFCCC, also posed a thought-provoking challenge to the room. “We create knowledge, but do the people on the frontlines of climate change understand it? Is it being shared in an inclusive manner?” he asked. He went on to reflect that even the word science carries assumptions: “We often don’t think about integrating knowledge systems,” reminding participants that climate solutions must value and reflect the realities of all communities, not just those represented in academic spaces.

The themes woven throughout Adaptation Futures spoke to the diversity and complexity of the adaptation landscape. Sessions ranged from Indigenous innovation and leadership, oceans and island futures, and resilient cities and infrastructure, through to the food–water–biodiversity nexus, health and wellbeing, climate finance, and the art of adaptation through communication and education. These conversations were strengthened by Kaupapa Taketake masterclasses and Kaupapa Motuhake sessions, which grounded global dialogue in local knowledge systems and Indigenous-led practice. Together, they highlighted not only where adaptation is heading, but who must be centred in shaping that future.

A standout moment for me was seeing local kaupapa elevated on a global stage, including “Cutting Our Own Track,” an adaptation action case study responding to multi-hazard risk and grounded in strong community leadership from the rural town of Westport — the mighty Kawatiri on the West Coast of Te Tai Poutini, and my hometown. Having this project recognised internationally, and setting the tone for the week, reaffirmed not only the importance of grassroots resilience but also the need for climate finance mechanisms that genuinely support communities to bring their projects to life.

Similarly, the close of the week highlighted “South Dunedin’s Future,” a kaupapa centred in a community of over 13,000 residents, exploring how to tolerate evolving risk through transparency, two-way dialogue, and iterative, community-led adaptation. I feel privileged to have lived in both of these communities; seeing their parallel journeys, each shaped by their own histories, geographies, and aspirations that is reinforced the importance of local nuance when sharing knowledge or designing adaptation strategies. Advice is never one-size-fits-all, and must always carry the asterisk of being tailored to your people, your whenua, and your context. Being able to convene global practitioners there were a multitude of golden nuggets shared across regions. These two intergenerational projects are powerful examples of what adaptation looks like in Aotearoa today; grounded, community-led, and future-focused.

I especially enjoyed learning from researchers whose work expanded my understanding of global adaptation challenges. Sessions on rethinking loss and damage after extreme events, particularly in Latin America and Indonesia that highlighted how communities are navigating compounding crises and redefining resilience on their own terms. In a future generations panel Awhina McGlinchey (Tokona te Rākai) powerfully reminded us that “the process we use to get to the future is the future we get,” emphasising the importance of intentional, inclusive approaches for future generations.

Hearing from Dr Richard Crichton of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) was another highlight. He discussed how their online programme empowering wāhine in Disaster Risk Reduction across the Asia–Pacific region has achieved a decade of impact, building capability remotely through the Sendai Framework. A paper presentation section spoke to how we can leverage emerging technologies within adaption work, such as the ‘Digital Twin’ by PJ Santa the Strategic Director of Urban Hydrologics. He discussed how you can enable community stewardship on blue/green infrastructure by having an app reliant on users to indicate work needed that then can be actioned by participatory paid workers that improves social cohesion, economic drive and tangible data to understand the watershed wider systems.

A key takeaway for me was the value of attending diverse workshops and hearing the unexpected parallels between places like Canada and Aotearoa. Michele Martin from the Waterloo Climate Institute underscored the urgent need for both technical and soft skills in the climate workforce and issued a clear challenge to universities to break down siloed departments, which are currently hampering the collaboration and innovation our future workforce desperately needs.

I also made sure to challenge myself, sitting in rooms of finance dialogue and how to unlock the barriers to finance local led action. It is interesting to remember that adaptation is such a new workstream, that for banks and other monitoring bodies the need for taxonomy within financials is crucial as the amount being dedicated to adaptation projects is unknown. David Hall from the Toha Network really set the scene, we need to “reframe adaptation investments as instead of ‘spending’ are actually ‘investing’ and create fiscal multipliers.”

I am greatly thankful to have been able to participate in a really insightful week and attend Adaptation Futures alongside Linda Faulkner, the New Zealand National Commission for UNESCO's Natural Sciences Commissioner. The National Commission mahi deeply reflects a commitment to culturally grounded and community-led approaches so aligning with the Adaptation Futures 2025 conference was really rewarding. As a UNESCO Aotearoa Youth Leader I look forward to continue to bring the kōrero shared back to our communities and knowledge share, grow and apply where possible. I thank this year's convenors and encourage youth to stay involved and get amongst local adaptation mahi within your local community.

WATCH HERE

Adaptation Futures Conference Streaming

There were a number of publicly streamed events, which can be viewed via the button below.